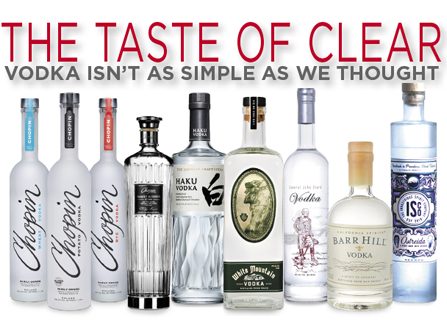

THE TASTE OF CLEAR-VODKA ISN’T AS SIMPLE AS WE THOUGHT

by LEW BRYSON

by LEW BRYSON

You may have missed a subtle but seismic shift in the world of vodka recently. It’s not your fault. It happened in April of 2O2O, when we all had other, much bigger things to think about. But it was kind of a big deal. The federal standards of identity, the regulations that say what makes vodka vodka, were changed. Specifically, the federal agency responsible for the regulations, the TTB, recognized that “the requirement that vodka be without distinctive character, aroma, taste, or color no longer reflects consumer expectations and should be eliminated.” As of April 2O2O, the regulatory requirement that vodka not possess distinctive character, aroma, taste, or color has been removed.

We’ve been given the green light to talk about what some of us have known for years. Vodka does have discernible flavor, and it comes from the feedstock, the stuff the spirit is made from…as long as it’s not distilled and filtered to death. Distillers have that choice. Some of them have already been making it, and now they can come out in the open and talk about what that means.

Tad Dorda founded the Polish vodka brand Chopin in 1993 for that reason. “Potatoes, rye, and wheat are the ingredients that vodka was originally made from in Poland and across the “vodka belt” in Eastern Europe, because these are ingredients that grow abundantly,” he explained. “But Chopin is the first vodka brand in the world to make vodka out of different ingredients to highlight different flavor profiles. “Our goal is to dispel the myth that ‘all vodka tastes the same,’ or that vodka has no taste,” he continued. “We believe that vodka, like other spirit categories, should have an appellation; an internationally recognized origin/geographical indication for products that have a specific quality and/or characteristic as a result of where they are produced and what they are produced from.”

That’s why Chopin makes four different vodkas: wheat, potato, rye, and the Family Reserve. The Family Reserve might be the most extreme vodka I’ve ever come across, and I’m not talking about filtering through diamond dust, or multiple distillations. This is about creating flavor, not taking it away. “Chopin Family Reserve is distilled from young potatoes,” Dorda said. “These potatoes are smaller and not fully formed and don’t have skin on them yet. Because of the lack of skin, they have a brighter and greener flavor profile and have not yet acquired the earthiness of a ‘late potato.’ We distilled the vodka in such a way as to leave as much of the flavor of the young potato as possible, so it has a very full flavor.” He continued, “Chopin Family Reserve is also rested in Polish oak barrels for two years which gives it a particularly mellow and pleasant taste, but it does not take on the color of the oak barrels.” Barrel-mellowed vodka! Dorda wants you to know: “This is not merely Chopin Potato vodka in a fancy bottle, it is a completely different product with a different production process and flavor profile.”

Grains like the wheat and rye Chopin uses in their other vodkas are what most of the world’s vodkas are made from. But Suntory, the Japanese distiller noted for their acclaimed whisky, makes their Haku vodka from a grain unlike the others. Haku is made from hakumai, short-grain Japanese white rice, and filtered through bamboo charcoal. “We selected pure white Japanese rice as it’s respected as a luxury,” explained Gardner Dunn, Suntory’s senior Japanese whisky ambassador. “The meticulous process required to mill and polish the rice attributes to the mild and subtly sweet flavor that it is revered for. [Bamboo charcoal filtration] preserves and enhances the rice’s delicately natural sweetness and subtle flavors.”

My first taste of Haku confirmed that Suntory understands the new vodka definitions. “While many spirits drinkers perceive vodka as a spirit without color, aroma or flavor, we are challenging that notion with Haku,” Dunn agreed. “I suggest new drinkers to try it neat before adding to a cocktail to fully appreciate the nuances the white rice and bamboo charcoal bring to the spirit.” Dunn also fit Haku right into the Japanese whisky tradition of the highball. “Our recommended highball recipe,” he said, “is the Haku-Hi which is Haku vodka (1.5 oz.), soda water (4.5 oz.) and a lemon peel, a light and refreshing drink that pairs perfectly with meals.” This crisp and sophisticated take on the common vodka-soda preserves and enhances the delicate flavor of the rice spirit.

Suntory and Dunn put Haku in the whiskey tradition, but little Tamworth Distillery (Tamworth, NH) got even more in the whiskey line with their White Mountain Vodka. It’s distilled from corn, malt, and rye: a bourbon mashbill vodka. It wasn’t always that way. “We had put out a 1OO% (partial malted) organic Harris White Wheat vodka,” said Tamworth distiller Jamie Oakes. But crisp and clean didn’t really stand out in the category, so the plan was to make a vodka with character.

“We recognize it’s a loaded topic, vodka with ‘character’,” he said. “We were producing our Neutral Grain Spirit from the same [bourbon mashbill]. There is a sweetness to corn that we really loved. We applied the carbon filter and brought it to 86 proof for a little balance with the mouthfeel, and made it our staple vodka. It is not . . . over-distilled, which allows it to carry the flavor of the corn. It often has legs and can be reminiscent of a really nice silver tequila.”

It’s also all organic, like the wheat vodka was. That puts the price up, but Oakes thinks customers understand, and are owed something more. “Organic is more expensive,” he admitted. “We really like the relationship we have built with our farmers and maltster friends. Distilling is an agricultural act, and we want to make sure the people growing good stuff get paid for their passion, especially growing in the arduous northeast! I think the consumer gets that we are doing things a little differently and are on first name basis with regional growers that are just as excited to produce as we are.”

A lot can be done with different strains of grain and potatoes. Still, grains and potatoes, no matter how carefully selected, no matter how they are put together or harvested, are not outside of expectations for vodka feedstocks. There are some more unusually-sourced vodkas on the market in Massachusetts. One of them is made from apples. “You look at the area and ask, ‘What sugar sources do we have here?’ Apples are a big one.” That’s Brian Ferguson, talking about how Flag Hill Distillery & Winery (Lee, NH) came to make their apple-based General John Stark Vodka. He bought the company in 2O15, but the original owners had bought then-bountiful apples in the early 2OOOs. They made a deal to buy all of an apple grower’s seconds. “We started buying 2O,OOO gallons of cider from him,” Ferguson said. There was an unexpected upside to this when they realized that the high malic acid content of the apples was converting to diacetyl during fermentation. Diacetyl is the stuff that gives movie theater popcorn its distinctive aroma and richness. “Diacetyl comes through the distillation,” Ferguson noted. “It has this buttery, almost candy finish, without any post-production additives.” Customers really took to it, which led to the unexpected downside.

“Cider has become more popular; cider to drink, and products from cider,” he said. “But we had this following around Stark, and even though apples have become outrageously expensive, we had to keep using apples. We’re paying about twice what we did three years ago.” He had no choice but to raise prices on the vodka. “It’s still our lowest-margin product,” Ferguson said. “Even though it’s expensive (MSRP is $33), it’s one of your best bang-for-the-buck in terms of what goes into it. It’s a unique vodka. It’s super-soft, super approachable, and that’s all derived naturally from fermentation.”

There’s another New England vodka with an unusual feedstock that you probably have heard of. I came across them not long after they started, and it was a sweet surprise. That’s right: Barr Hill Vodka, made from raw honey by Caledonia Spirits (Montpelier, VT). The interesting twist about Barr Hill’s honey feedstock for me is that it captures the idea of terroir – in a vodka! – in a way that becomes instantly understandable. Honey is subtly flavored by the flowers that are around the hives: buckwheat honey, clover honey, wildflower honey. If the hives are in only one area, that honey, and whatever is made from it, tastes uniquely of that area.

Sam Nelis, the beverage manager of Barr Hill, pinned that in the first thing he told me. “Barr Hill was founded by Todd, a beekeeper and Ryan, a distiller. They were passionate about bringing their local terroir into the craft distilling industry and using raw honey was their way of doing that.” Barr Hill never really respected the ‘odorless, colorless, tasteless’ vodka dogma. Their process makes that clear. “We never heat the honey prior to fermentation and we never distill more than twice,” Nelis said. “Our technique preserves the rich aromatics of nectar, delivering the floral depth of wildflower fields straight to your glass.” I can vouch for that. It’s subtle, as you’d want it in a vodka, but it’s definitely there.

I left the oddest feedstock for last. Industrious Spirit Company (ISCO), a relatively new distiller in Providence, Rhode Island, makes their Ostreida vodka from corn . . . and oysters. It’s not flavored with oysters post-production, the oysters go right in the still. Shells and all? “Can’t tell you,” said CEO Manya Rubinstein. “We did a lot of experimentation, but we found the one way that works best. And nothing’s added after distillation except water. It’s not oyster-infused.” The base spirit is made by ISCO from organic corn from Stone Hills Farm in upstate New York. “We create the neutral spirit, a two month process,” she said, “and then on the finishing run, we introduce the oysters to the still. They have to be super-fresh, preferably harvested that morning.”

I’m nosing a sample right now, and it’s there, but it’s not crazy. “This isn’t a spirit where you’re like, ‘Is there oyster in this?’ But it’s not overwhelming,” Rubinstein said. “You get oyster on the nose, and our corn spirit is round and smooth and an implied sweetness, and then there’s this minerality. It’s almost like a pre-made dirty Martini.”

Just like a good oyster bar, Ostreida (it’s ‘ah-STRIDE-uh’, from the Latin for ‘oyster’) tells you what you’re tasting. “We discovered through experimentation that if you use a different type of oyster, that comes through the distillation process,” she said. “So we started tagging bottles with tags that show where they were harvested, a specific product that tells a specific story.” My sample was made with oysters from the Matunuck Oyster Farm in South Kingstown, RI. Rubinstein referred to this distinction among different oysters from different areas as merroir, a rare but real French word that is the coastal equivalent of terroir, and applies specifically to oysters. That leads to the question: can an idea already as subtle and connoisseur-directed as terroir really be found at the far end of the full process and distillation of vodka, which was until recently celebrated for being odorless and tasteless?

I like something Brian Ferguson at Flag Hill said when we were digging into that. If you’re paying more than usual for vodka, he said, “you want to taste the vodka. There’s a lot of difference between where vodka exists chemically and where vodka exists legally. There’s a lot that happens in that little margin.” Distillers can push vodka right up to the limits of distillation (which is significantly less than 1OO% alcohol…but that’s a whole other chemical discussion)…but they don’t have to. And that’s where that ‘little margin’ Ferguson talks about happens, and that’s where these spirits find their life.

Does it make a real difference? More importantly, does it make a real difference to your customers? Sometimes it’s the proposition of a unique process that can hook people. “It’s the first ever vodka distilled with oysters in the US, maybe the world,” Rubinstein said of Ostreida. But her vodka is also made with organic corn, combined with farmed, sustainable shellfish. That’s something that most of these vodkas offer: a local connection that you can actually taste. Tamworth uses locally-grown, organic grains. Barr Hill harvests honey from their own bees; Flag Hill buys local apples. Tad Dorda grows much of the grain and potatoes for Chopin on the fields around the distillery. Haku has a deeply cultural connection that makes a unique fusion of Japanese ingredients and European spirit traditions, very different from traditional Japanese grain spirits like shochu.

The great thing about vodkas like these is that they offer something Tad Dorda thinks is missing from the whole concept of vodka in America. “I think there is still a huge education component missing around where vodka originated and what ingredients are used to make vodka,” he said. “We believe that vodka is nuanced and that there is a story to tell here. This…reinforces our mission to shift the conversation around vodka from being a tasteless, colorless, odorless mixer synonymous with nightlife to an original Polish spirit that’s meant to be savored, appreciated, collected, and discussed.”

Vodka hasn’t changed. But how we see it has, and more importantly, how we smell it, taste it, and think about it will change. Vodka will always be a commodity, a basic purchase for everyday mixing. But thanks to our changing, evolving tastes for spirits, vodka is becoming more than that. It’s more interesting than many of us ever realized.

ON THE OTHER HAND . . . If you’re a drinker that still wants your vodka to be nothing but ‘colorless, odorless, tasteless,’ have I got a bottle for you! Air Vodka is literally made from nothing but air and water, fed by solar-powered electricity. Before you say it’s impossible, you should know two things. The ‘air’ is actually carbon dioxide (largely “harvested” from fermentation at other industries); and the science is based on an accidental discovery that was made in 2O16 at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Sound more possible now?

The scientists at Oak Ridge…well, to make it very simple, they found that if they put CO2 dissolved in water – just like I get out of my SodaStream – in the presence of nanoscale particles of copper embedded in a substrate of carbon spikes, and zapped it with electricity, there was a catalytic reaction that turned the sparkling water into ethanol. Not quite water into wine, but almost miraculous.

The Air Company (Brooklyn, NY) took this phenomenon and scaled it into a workable production system for making ‘carbon-negative’ alcohols. Their Carbon Conversion Reactor gets flows of CO2 and hydrogen, a reaction occurs, and “an alcohol mixture” is created. The mixture is distilled to separate out the ethanol (the Oak Ridge process produced a 63% ethanol output), which is used for Air Vodka, perfume bases, and other alcohol-based products. Not inconsequentially, the distillation also meets the regulatory requirements for vodka, which require distillation but say nothing about fermentation.

What about that “carbon-negative” part? An Air Company spokesperson told me that the entire process – CO2 capture, purification, compression and transportation – emits around O.1 kg of CO2 per 1 kg of CO2 used: O.9 kg CO2 taken out of the air. The hydrogen production, and the ethanol conversion process itself, both run on renewable energy. Making Air Vodka takes more carbon out of the air than it puts in. They plan to open a new facility in Brooklyn this year, which will boost production tenfold. They hope to be in Massachusetts “sooner rather than later.”

GIN CAN PLAY TOO It’s an argument that’s as provocative as asking whether a hot dog is a sandwich: is gin a flavored vodka? In the context of the main article, then, can a different feedstock change a gin? Brian Ferguson at Flag Hill has a Karner Blue Gin that he thinks has a fundamental difference. “Almost all gin is made from GNS: grain neutral spirit. We use apple neutral spirit. What you get is that the apples impart this really pleasant finish…that creamy finish like you get in our vodka. It’s really, really nice. There are a lot of great gin producers in America. These little details are the defining differences.”

The first time I ever noticed a difference in gins based on what the actual spirit was made from, as opposed to the botanicals, was St. George Dry Rye Gin, from St. George Spirits in Alameda, CA. The distiller there, Lance Winters, noted that they made two different gins, but wanted to make “a massive quantitative change, but still be gin. “As we started mentally exploring what different base spirits to try, rye rose to the top,” he recalled. “Its potential for peppery notes provide commonality with the juniper, and an excellent basis to choose the remaining botanicals (coriander, caraway, black pepper, lime peel and grapefruit peel). In addition to the complimentary qualities of the rye, it has a contrasting maltiness that contributes that rich, creamy mouthfeel.”

Just like in vodka, how you make your spirit makes a difference. But Barr Hill took the difference they made in their vodka, the raw honey feedstock, and added it directly to their gin. Barr Hill’s Gin, a strikingly different gin, is grain spirit that is finished with some of that raw honey. “The goal is to get the 1OO-15O wildflowers from the honey to give the gin a botanical pop,” said Barr Hill’s Sam Nelis. “It’s a very small percentage that goes into the gin. We did not want to make an overly sweet gin, but we love the local botanicals present in the raw honey so that’s why we use it!”

These are all ways a distiller can make a different spirit, a unique spirit, an interesting spirit. It’s not that one way is a better way to do it, but that they are choices. I liked the way Lance Winters put it. “At the end of the day,” he said, “a base spirit is much like a substrate on which to paint. Whereas a neutral spirit is like a bright white canvas which lets the colors of the botanicals read true, the black velvet of the rye needs to be taken into account and botanicals adjusted accordingly.”