TAMING TANNAT IN THE LAND OF PAINTED BIRDS

ASKED to explain why wine can capture and hold the interest – even the fascination – of so many and so disparate a spectrum, I thought that, after the good tastes, social lubrication, food enhancement, and health promotion, it must be the infinite variety. There is always another vineyard, another vintage, another grape variety, another innovation in nurturing vines or fermentation. Well, today is a treat for most of us: we are to be introduced to a new country, Uruguay, as source of fine wine, and an unfamiliar grape, tannat. This has been precipitated by the recent seminar and tasting in Boston featuring 16 talented Uruguayan vintners and speaker Gilles de Chambure, master sommelier and wine educator.

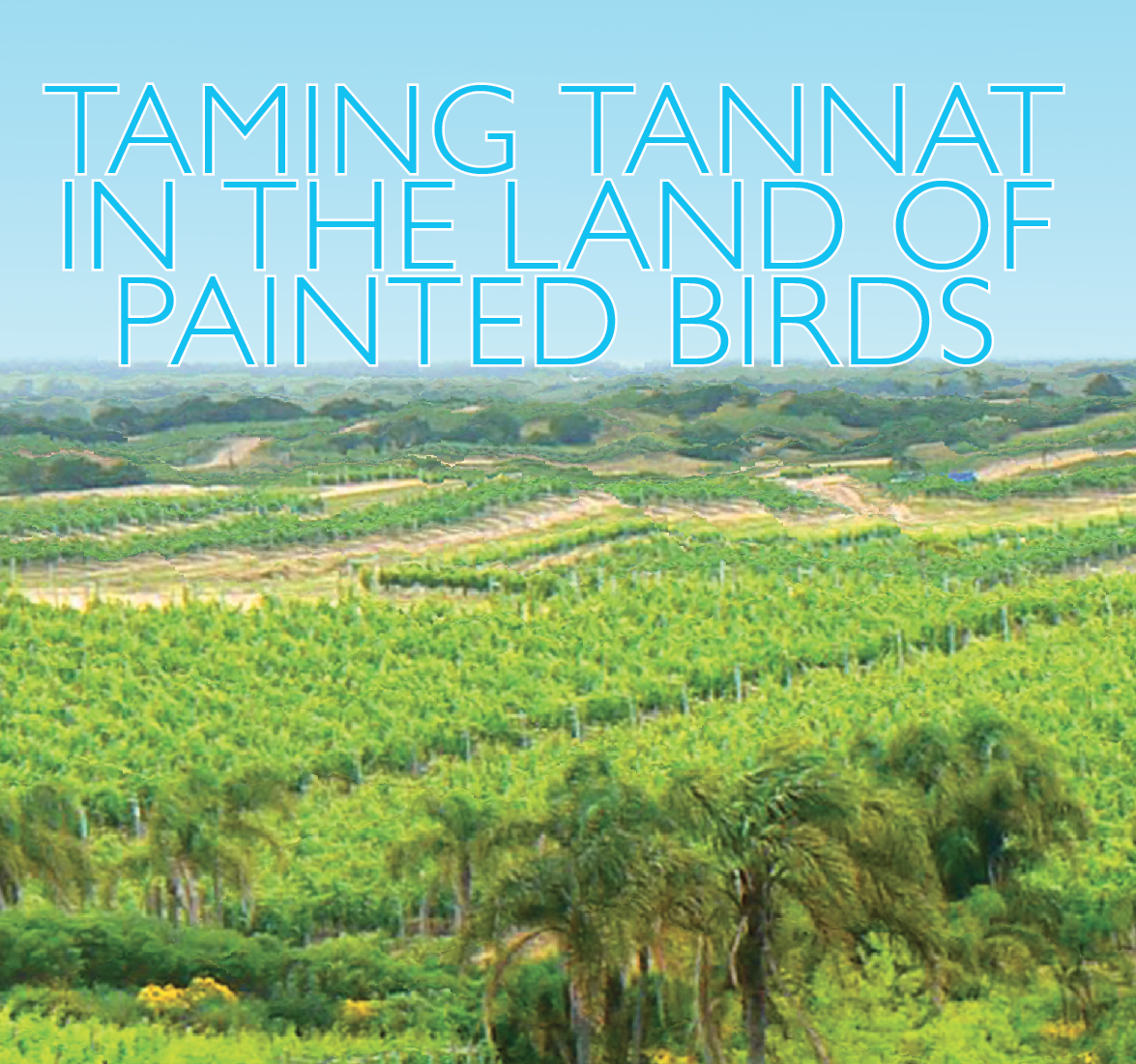

Uruguay (officially, La República oriental del Uruguay, in which the “Uruguay” originally referred to the river) is a small country wedged like a cork into the Atlantic side of South America between Brazil and Argentina. Its name in an indigenous language means “river or land of painted birds”. Lying between the 3oth and 35th parallels of latitude, it is temperate and humid, cooled by the south-Atlantic ocean current and the winds that blow from over it. In addition to the Rio Negro, the Rio Uruguay and others, the great estuary of the Rio de la Plata contributes to the pervasive aquatic influence. The country is enviably unpolluted. Hilly, nowhere mountainous, Uruguay – although quite urbanized – is primarily an agricultural economy, with beef its pride and chief export.

The 68,ooo square miles (just under the size of Washington) are occupied by 3.4 million people (1.3 million in Montevideo, the capital) and more than 12 million cows. The population is largely of European descent, especially Spanish, Basque, Catalan, and Italian. After a tumultuous early history, and with the exception of a very difficult few years during the late 2oth century, Uruguay has settled down as a peaceful, democratic, educated society with a stabile middle class. I’m informed that women are prominent in commerce, including the wine trade. Abortion and same-sex marriage are legal. Tariffs are high. It is the only country that has set about to legalize the production, sale and use of marijuana.

Though the Spaniards brought winemaking to Uruguay in the 18th century, nothing notable ensued until 187o, when French Basque émigré Pascal Harriague and others began to plant tannat, which likely immigrated from southwestern France via Argentina. It quickly took hold and became the national grape. It was even called “Harriague” at one time. one third of Uruguay’s 22,25o acres of vines are now bearing tannat (43 percent of red grapes), more than the rest of the world’s producers combined. The wines have improved in quality and evolved in character through developments in the vineyards and in the wineries. The grape has changed too, during its long sojourn in the relatively moist vineyards of South America, or perhaps it has also changed in its native home of origin in southwestern France (Madiran, Irouléguy). This thick-skinned grape is no longer possessed of the fierce tannins that named its ancestor. It is said that recently imported clones from France are riper, yielding more alcohol, less acidity than those that came long ago. Unresolved are ongoing discussions about whether and how to blend the two types.

The Uruguayan Tannats I sampled are mostly deep in color, may smell of blackberry, and taste of pure uncomplicated fruit, perhaps with a hint of spice in some (possibly from oak). I believe that especially new-oak exposure should be judicious. I encountered both French and American oak aging, as well as wines matured in inert containers. The wines are ideal company for Uruguayan or other beef. I don’t know that the high concentrations of hopefully healthful polyphenols reported in the Tannats of southwestern France have been reconfirmed in Uruguay, nor whether that could translate into cardiovascular health and long life as has been claimed. one of the maneuvers used to tame tannins in the Tannat has been blending it with almost any other red you can name. I tasted one grower’s graceful blend with Viognier, inspired by Côte-Rôtie. Made sometimes as a rosé and rarely as a credible Port-like dessert wine, Uruguayan Tannat prepared as a sturdy, dry red should evoke no fear. It gives us another sound choice – and at moderate price.

Tannat is not Uruguay’s only wine. The country’s 3ooo growers and 2oo wineries produce 1o million cases annually, 72 percent red. Liking their own wine, 17th in the world in per capita consumption, Uruguayans export only five percent of production, though one might guess they plan to raise both. The producers seem very quality conscious. Vines are dry farmed. Grapes are hand harvested. Vineyards and wineries are small family businesses rather than coops or large companies. Although bound to European tradition, wine production is technologically modern. The production areas are spread through much of the country, with 6o percent in Canelones, the department in the maritime south surrounding Montevideo. Soils vary, prominently clay-rich limestone. other than tannat, you will find Bordelais reds, tempranillo, syrah, pinot noir, zinfandel, chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, sémillon, albariño, viognier, and adventurous crosses and blends. Uruguay now has a wine trail for interested visitors (uruguaywinetours.com).

The consistently high quality

of the 75 wines exhibited at the road show was impressive, yet, to an American, one winery was of parochial interest. owned and directed by Californian Leslie Fellows, Artesana Winery grows 2o acres of tannat, merlot, cabernet franc, and the only zinfandel in Uruguay in Las Brujas (“witches”), 3o miles north of Montevideo in the Department of Canelones. Leslie and her uncle had a Uruguayan vinous epiphany during a trip here, then set the winery project going in 2oo7. Tannat, the lead grape, bottled as a single variety and as mollified by the others, has won awards in the US. The winemakers are two Uruguayan women, Analia Lazaneo and Vanentina Gatti, who inspired the naming of the winery. Artesana is Spanish feminine for “artisan”, which describes in a word their practices in the vineyards and winery. Currently producing 2ooo cases per year and exporting 3o percent to the US, Artesana is expected to double production eventually. I’d hope to see more of its wines and those of its colleagues in our market.