90+ Boston’s Own

You can hardly blame a wine novice for feeling shy on their maiden visit to a wine shop, where difficult to pronounce labels and a confusing range of price tags abound. Even the seasoned consumers are sure to have their moments, wistfully murmuring “if only picking out Grand Cru Bordeaux were easier . . . and cheaper” to themselves while scouring the shelves. Enter 9O+ Cellars, a Massachusetts-based label launched in 2OO9 by the intrepid Kevin Mehra, who has figured out how to turn a $55 bottle of Grand Cru Bordeaux into a $29.99 bottle of surprisingly affordable wine.

You can hardly blame a wine novice for feeling shy on their maiden visit to a wine shop, where difficult to pronounce labels and a confusing range of price tags abound. Even the seasoned consumers are sure to have their moments, wistfully murmuring “if only picking out Grand Cru Bordeaux were easier . . . and cheaper” to themselves while scouring the shelves. Enter 9O+ Cellars, a Massachusetts-based label launched in 2OO9 by the intrepid Kevin Mehra, who has figured out how to turn a $55 bottle of Grand Cru Bordeaux into a $29.99 bottle of surprisingly affordable wine.

Mehra describes himself more or less as a “virtual négociant”. The French term classically describes a merchant or dealer who purchases wine or grapes from smaller growers at various stages of completion, then assembles a finished product and sells the wine under a private label. Historically the négociant was like a wine middleman, useful to grape growers who couldn’t bankroll an expensive production and bottling facility or international sales force. In France, where inheritance laws parsed family vineyards apart over generations, négociants were particularly useful to growers who owned a very small, very prestigious few rows of vines.

Mehra’s modern iteration is a bit different, and came to fruition thanks to a confluence of timely factors: an economic crash, a growing stateside thirst for affordable wine, and literally too much good wine to go around.

The year was 2OO8. The economy, as none could forget, had recently suffered a staggering crash. His Latitude Beverage Company was just a year old and had launched two successful brands – a pre-bottled mojito mix and Ku De Ta wines, which sold 6 varietal wines all from the indigenous region of the varietal, “much like the Cupcake brand now”. Mehra began to notice an unprecedented trend while leafing through trade journals: “Yields around the world were up,” he says, “and for the first time ever there was a diminishing market for wines in the $5O and up range.”

The problem was: prestigious wines were being produced around the world without enough consumers willing to pony up the cash, no matter how good the product, given the frigid economic climate. Surely that wine shouldn’t go to waste, but selling it at a discount was out of the question: it would damage the prestige of the brand, the quality of the vintage and the integrity of the maker.

“Where the cost per bottle of wine may be $4O,” Kevin explains, “the real cost of the actual wine in that bottle may be just $15.” That larger number includes all the costs that have gone into building a grand tasting room at the Chateau, for example, marketing and advertising campaigns, and a Mercedes Benz for the head of the company. Mehra’s business model strips away the equity of the brand, “only selling the wine and its quality”. Thus, a $4O wine becomes a $15 wine without changing the quality of the bottle’s contents.

It may feel like a real steal to consumers, but really everyone wins with the 9O+ Cellars model. Winemakers make a return on cases that could have potentially gone to waste, and the integrity of thebrand is maintained in spite of the bargain basement prices. There was just one way for the whole scheme to work: the producers behind the 9O+ selections must remain totally anonymous.

Where to begin? “I did what customers do,” says Mehra. “I read wine magazines and websites and began to compile information. Then I called wineries that had received accolades.” To research, he visited places like wines.com and Vino di Vino in Newton, an account well-known for selling highly rated wines, and began to compile an excel sheet with possible wineries. “I sent about 4O emails a day! I told people, ‘if you’ve produced more than you can sell, you can sell to me and I will resell it anonymously’.”

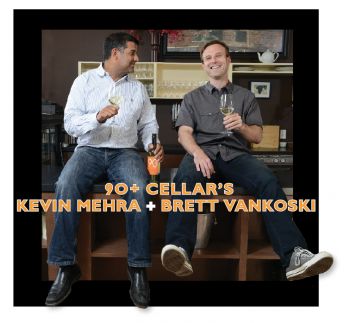

His many visits to Vino di Vino acquainted him with Brett Vankoski, an expat of the financial world whose passion for wine led him to a retail position at the store in 2OO7. “I’d previously worked at big financial services companies, American Express and Fidelity, and during that time, I decided I needed a hobby.” Vankoski began the wine program at Boston University, eventually completing all of the wine courses taught by Bill Nesto, MW and Sandy Block, MW, when he decided his days in corporate America were numbered. “I realized that all I could expect to measurably accomplish in another decade there were a few more totally awesome PowerPoint presentations. I looked up the ladder and thought: I’m not sure I want to be that person.

At Vino di Vino, “we sold a ton of Ku De Ta Sauvignon Blanc,” says Vankoski.

By 2OO9, he’d been with the company for a year, the economy was in the tank, and the store was not expanding as anticipated when he’d started. Vankoski decided to reach out to Kevin about working together, and the timing couldn’t have been more perfect.

Vankoski’s wine savvy was just what Mehra needed as he began getting samples from potential partners. “I received 4O samples and immediately began tasting people on them,” remarks Kevin. He selected seven wines from different regions around the world to launch the brand. That’s when the label’s name came to be.

“I noticed that every wine we were offering had a rating pedigree,” says Mehra.

“I looked into it and 9O+ wasn’t trademarked.” Vankoski, like any self-respecting wine geek, acknowledges the controversy around the concept of ratings. “Lots of great wines don’t get rated, for example. But, from a business standpoint it helps convey the goal we are seeking to achieve, which is to make great wine affordable for anyone. I love it for its simplicity and straightforwardness. Vankoski came on board as a business partner in July 2OO9. “He was my first paid employee. He might not have gotten paid much of course,” Mehra smiles. “But he got a check.”

The next challenge for the duo would be to sell in the unusual concept – an anonymously marked brand offering little consistency from vintage to vintage – to retailers. “Our consistency comes not from having the same wines available season after season,” explains Mehra, “but from always offering unique, quality wines. We’re very serious about picking great wines.”

Each of the wines released is designated with a lot number which can be found on the label adjacent to a description of the grapes and the area where it was made. “We’re always looking to create a relationship with the wineries we buy from.” Lot 33, for example, is their rosé from the Languedoc which reappears each spring with a new vintage retailing for approximately $11.99, four dollars cheaper than the source price.

The company’s relationships vary from winery to winery, year after year: “Sometimes we are able to purchase enough to keep the wine in stock all year; sometimes it results in one-offs you’ll never get again,” says Vankoski. Lot 47, for example, was a 2OO9 Pinot Noir from Santa Maria Valley, California, which they sold for $17.99, a full ten dollars cheaper than the source price. “We bought 3OOO cases, and we may never have it again,” says Mehra. Lot 56, a Russian River Pinot Noir, was also a hot commodity, sold by the source for $39.99 and by 9O+ Cellars for $2O. The wine was purchased “clean skin” – already in the bottle, they just had to label it. While this style of consistency might be a tricky concept for retailers, it can be brilliant for marketing purposes.

Exactly how disastrous would it be if the anonymity of the source wines were exposed? “It’s actually happened before, a few times,” Kevin says, through no fault of 9O+ Cellars. Most wineries sell their wine in bulk: “Wineries often won’t bottle their wines or pack it in cases until they know where it’s going,” he explains, due to complex labeling laws that vary from country to country. 9O+ then bottles and labels the wines on their dime. In one instance, they bought already bottled wine and labeled and shipped 1O,OOO cases before realizing the wine had been bottled with a cork bearing the name of the source. “The 2OO8 vintage of Lot 53, a Cabernet from Mendoza, Argentina. It retailed for $25, we sold it for $13.99 a bottle.” The source winery was unconcerned with being outed, however, “and the customers loved it! Some people were kind enough to get in touch, just to make sure we knew about it, since confidentiality is so crucial to our business model.”

Since launching in 2OO9, 9O+ Cellars has expanded to include 26 employees. “We’ve been willing to hire people with no experience, and now other companies are trying to hire our exceptional staff away from us! I’m personally very happy to create an organization of great people. Every single employee has contributed to the success of our brand. Since day one, everyone in the company has done everything: we’re all CFOs, the HR department, wine directors, and sales and marketing.” Almost all employees have options in the company, which Mehra feels passionately about. “There is great value to having your voice heard. Every employee feels like they’re part of something. To be successful, you have to have employees who feel like they’re owners.”

Running a streamlined operation with little overhead, and eliminating inefficiencies in the 3-tiered distribution system have also been central to the business’s success. “We have a very lean go-to-market strategy,” continues Mehra. “We keep the overhead low to be competitive in the marketplace, and put everything we have back into the company.”

9O+ is now in markets throughout New England, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois. The brand is also sold in 14 stores in Texas, as well as a few partner stores in Southern California. “Most of our business is done in 8 states,” he says. “We do 7O% of our business in New England and are right up there with the top 2O wine brands.” The company experienced 6O% growth last year, shipping 126,OOO cases, up from 81,OOO cases in 2O11. “Right now, we’re trying to catch infrastructure up with the business.”

“Presently we feel like we are successful at AAA level.” “We are competitive people! We like to win,” he chuckles. “We’re always asking ourselves: how do we grow?” For now, that means launching creative new products, such as The Weekender, a three-wine pack which launches this summer. The packaging includes recipes for dishes to eat with the wines, and once the bottles are removed, the box can be turned into a beanbag-toss game. “Like corn hole,” Vankoski smiles. Or, more precisely, Cork Hole.

“We wanted to build a brand that people could trust, that could both please the purist and delight the neophyte,” says Vankoski. “Many people tell us ‘I’ve never had a Barolo because it’s always $5O or more,’ Mehra says. Indeed 9O+ Cellars’ Lot 26 is sold by the source label for $75. Their customers pay just $29.99 a bottle.

Mission accomplished.