BEER 101+

Knowing a little bit about a subject tends to spark a desire to learn more. Whether a detail about the playing style of John Coltrane, the brushstroke methods of Georges Seurat, or the hand-eye coordination of Peyton Manning, a little extra knowledge adds a new level of appreciation and fun to any experience. Learning new pieces of information about beer is like putting together pieces in a puzzle. When you learn about its core ingredients, for example, you can understand how each of the parts fits together to form the foamy final product that sits before you.

At its base, beer is an alcoholic beverage made from a mixture of water and malted cereal grain, such as barley or wheat, flavored with hops, and then fermented with yeast. While creative modern brewers have vastly increased the list of possible ingredients, these core four ingredients comprise the majority of beer made today. A few larger breweries use adjuncts, such as rice and corn, to often lighten the bodies and flavor profiles of their beers, a practice derided by beer geeks and purists who believe such efforts reduce the overall flavor of the beers. And while some craft brewers have gone off the deep end with their esoteric creations, including garlic and beet beers, most brewers restrict their ingredients to the key four with occasional simple additions.

Understanding how the ingredients in beer interact is crucial to differentiating between the many available beer styles. Commonly referred to as the soul of beer, malt is a workhorse ingredient that provides the base for all the other ingredients. Hops are often called the spice of beer, providing splashes of flavor against the malt backdrop. In comparison to wine, grain replaces grapes as the primary fermentable ingredient in beer. To create brewing malt, maltsters (including Samuel Adams in his day) wet barley until it germinates, then slowly dry it at controlled temperatures, causing the barley’s starches to create a sugar conversion. Maltsters are able to create different malt types based upon the kilning process length, with longer periods creating darker colored malts and resulting in roasted flavors.

In designing a beer recipe, each brewer carefully chooses between malt varieties in order to select the color and flavor of the final beer. Brewers employ specialty grains, including chocolate and black malts, to create dark beers such as porters and stouts, while less roasted pale malts lighten Pilsener, Pale Ale, and Amber.

Brewers next add pellet or whole leaf hops, close relatives of the Cannabis plant, to bring a balance of bitterness and earthy aromas to the beer. As with the use of spices in making a stew, a brewer must artfully select the hops to use and determine the point during the process at which to add them. Early hop additions during the boil impart bitterness, with middle additions contributing flavor, and final additions providing aroma. Hops also work as a natural preservative agent in beer, fighting against spoilage.

While malt, yeast, and hops all significantly affect the qualities of the final product, the particular character of the brewing water is also important. As water comprises more than 9O-percent of beer, the mineral content of a brewer’s water supply heavily influences the final flavor. In Burton-on-Trent in England, the high calcium and sulfate content of the region’s brewing water provides the qualities needed for strong flavored pale ales. In contrast, Pilsen in the Czech Republic’s soft water gave birth to the region’s world-famous crisp lagers.

After the brewer develops a recipe and the materials arrive at the brewhouse, the actual brewing process finally begins. The brewer mills the malted grain to finely crush it into grist in order to withdraw the sugars that the yeast will feast upon in fermentation. The brewer then mixes the grist with water in a large brewing vessel, called the mash tun, where the mixture is gradually heated to a set temperature, which converts the malted barley’s starches into sugars. This process is crucial to the head retention and body of the resulting beer. The brewer then transfers the mix to another large brewing vessel, called the lauter tun, where the brewer adds hot water to wash the sugars from the malt, resulting in thick, sweet liquid called wort. A false bottom in the lauter tun strains the spent grain from the water and allows the wort to transfer to the brew kettle. In an eco-friendly gesture, many breweries donate or sell their spent barley to local farmers for use in feeding their livestock.

In the kettle, the brewer brings the wort to a rolling boil and then adds hops at select intervals to achieve the desired flavors and aromas. After the boil finishes, the brewer transfers the wort to the fermentation tanks, where yeast is pitched to start fermentation. During fermentation, the yeast eats the sugars in the wort and creates the wonderful byproduct of alcohol, resulting in beer. For thousands of years, early brewers had no conception of what added that great kick to their drinks, where they unknowingly relied upon airborne yeast strains to inoculate their brews. It took French scientist Louis Pasteur, known more for his work with milk bacteria, to discover that yeast microorganisms held the secret of fermentation. By establishing the existence of yeast cells in his 1876 Études sur la Bière (Studies Concerning Beer), Pasteur helped brewers exercise greater control over fermentation and the resulting products of their efforts.

Another defining moment in the life of beer occurs when the brewer chooses the type of yeast strain to be used, generally either ale or lager. Ales are beers whose yeast collects at the top of the vessel and that best survive fermentation at warmer temperatures. But as with trying to classify a wide ranging art style in a single phrase, no short description can hope to capture the essence of such a broad category of beers. Generally speaking, ale yeasts produce fruitier beers. Lagers yeasts collect at the bottom of the brewing vessel and undergo fermentation at cooler temperatures. The cool lagering process generally produces a smoother final product that possesses less aggressive aromas and flavors. The type of yeast used and fermentation temperature also influence the length of the aging process. Ales generally age for one to three weeks, while lagers age for six to eight weeks. Certain high-powered ale and lager styles can age for a year or longer in order to mellow or fully develop their flavor profiles.

Pick a flavor, any flavor, and there is a beer that tastes like it. Choose any aroma you favor and an ale or lager exists to mimic its essence and please your palate in the process. Endlessly creative American brewers have concocted all manner of delicious and nuanced beverages, from India Pale Ales chock full of grapefruit and orange aromas to Belgian-style Tripels that taste like bananas and Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit gum to stouts brimming with smooth, inviting coffee and chocolate notes. Much like young Charlie entering Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, if you can imagine the beer you want to drink, imaginative brewers can brew it. From quiet, sipping, and cool lagers to palate bullying hop monsters and every hint of floral fruit, bready sweetness, or funky flavor in-between, the wide world of American brewing creativity is bound only by the imaginations of its passionate brewers and the courage of adventurous consumers.

While there is no need for consumers to understand the intricacies of dozens of beer styles, a little knowledge can enhance their enjoyment, like knowing the songs at a concert. Taking time to explain a little history about the dozens of beer styles you can find in most local stores and bars can help consumers branch out from their regular brands.

For those consumers who generally choose lighter flavors beers or perhaps still carry out six or twelve packs of Bud, Miller, and Coors products, try suggesting a couple of straightforward German Helles style beers. Especially popular in and around Munich, this style was developed in the late nineteenth-century by Bavarian brewers to compete with their Czech Pilsener rivals. The classic style focuses on a mild yet grainy malt flavors and often possess a light and sometimes spicy hop bitterness. A touch hoppy, the smooth-drinking bready Munich malt flavor is key to the popularity of the Helles style, which is often sold under the generic Lager designation in southern Germany. With a sustainable, tight white head of foam and striking golden color, a glass of the clean, medium-bodied Helles is sure to catch your customer’s eye and convince them to order another round.

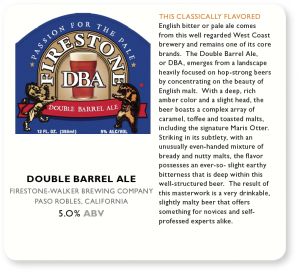

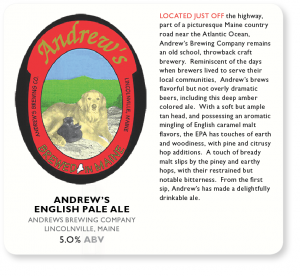

Click on Images Below For Tasting Notes.