Bourbon

One

thing’s for sure: this ain’t your daddy’s

bourbon.

But some of it

is Pappy’s bourbon – Pappy Van Winkle, that is. And the

bourbon that still bears his name is a good example of

what’s going on in the bourbon business today. Pappy’s

grandson, Julian Van Winkle III, has been in the business

since 1977, and now he’s in a joint venture with Buffalo

Trace distillery, producing a line of aged, wheated bourbons

(and an aged rye; see sidebar) at premium prices. Let other

distillers argue over who started the “small batch” bourbon

category, Julian Van Winkle’s on his board and riding the

wave.

“From our side,

we’re selling every drop we’ve got,” said Van Winkle, who

spent the last 2O years tracking down barrels and tanks of

bulk whiskey for sale, much of it from his grandfather’s

now-closed Stitzel-Weller distillery. “It’s all allocated,

we know where every case is going. Price increases don’t

seem to slow it down at all. It’s a little scary, because it

might be like the housing industry: it’s gonna blow up one

of these days.”

Given the long

decline American straight whiskeys (and we’ll use that term

and ‘bourbon’ interchangeably for the sake of brevity) have

been on, it looks like things are blowing up now. Jack

Daniel’s long streak of solid growth against the category

has finally turned into a category leader, as other brands

show positive action as well. The major sales in the

category continue to come from Jack Daniel’s Old No.7 and

Jim Beam White Label, with over 5O% of the market between

them. Evan Williams and Early Times contribute another 13%

or so, and the other brands together account for the other

third.

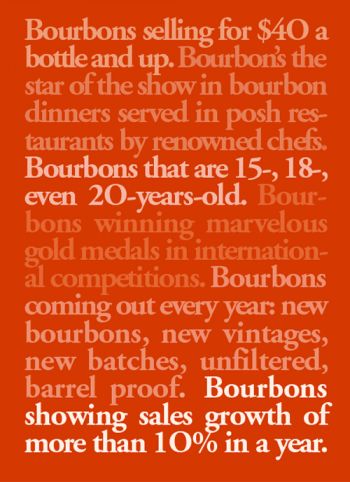

To say that

overall growth of the category is “blowing up” is an

exaggeration – there have been very modest gains the past

two years. But there’s a lot to be said for holding steady,

and the growth in the premium and super-premium brands has

been nothing short of remarkable. “We’ve seen incredible

growth in the super premiums,” said Larry Kass, with Heaven

Hill distillers. “We’re doing very, very well in

Massachusetts.”

“There are three

dynamics at work there,” he explained. “First, the economy

has been rolling. Second, super premium spirits have been

doing well because they taste great: if you buy better, the

experience is better. I also think that we’re atoning for

sins of the past by educating people about what makes

special bourbons special, and so why it’s right to expect to

pay more for them. It certainly worked for Scotch and

tequila. Our super-premium Bourbons are really great, but on

the low end there’s no such thing as a “mixto” bourbon. Even

the standard brands are pretty good stuff. That’s a good

thing in our favor.”

Wayne Rose,

Brown-Forman’s Woodford Reserve man, believes that there’s

plenty of headroom to this rush to super-premium bourbon.

“We don’t believe it’s going to slow down any time soon,” he

said. “For example, about 9% of the Scotch business is at

the super premium level, tequila is about 13% super premium,

but super premium bourbon is only about 2.7% (of the

category). There’s a lot of consumer interest in

super-premium products, and bourbon is just starting to

capitalize on that.”

Rose gives a lot

of credit for this to overall better whiskeys. “Why are

people willing to pay more for a bourbon?” he asked. “We’ve

finally given them a reason to: it’s better product. The

whiskey is better than it was even 1O years ago. Everyone’s

making better bourbon than they did. They’re actively

competing for awards. There’s real pride, and it’s fun. The

barrels that are selected for the premium whiskeys are truly

premium barrels. We’ve hit on something consumers are

looking for – a higher end – and now there are a number of

products that are filling that niche. Some whiskeys that I

don’t care for personally, I still realize that they are

made that way for a reason, they’re not just what they had

in the warehouse.”

Julian Van

Winkle sometimes feels like he’s paying for some of those

ten-years-ago bourbons. “We are always seeing people who’ve

tried something they didn’t like a long time ago and think

they don’t like bourbon,” he said, “and then they try ours,

or something else nice, and they say ‘Wow, that’s totally

different from what I expected!’ We get a lot of new

customers that way.”

People still

aren’t paying – and distilleries aren’t charging – the kind

of lofty prices single malt scotch and exceptional 1OO%

agave tequilas can command. What’s the deal? Are bourbons

just not worth the money?

That’s not

really it; it’s a self-inflicted injury that dates back

decades, when bourbon distillers slashed prices in a

desperate attempt to stay open. “The bourbon industry dug

itself into a hole back in the ‘5Os and ‘6Os,” said Kris

Comstock, who’s with Buffalo Trace distillery, “and we’re

just digging out now. You walk in a store and the premium

bourbon section is mostly $2O to $3O. If I didn’t work for a

distillery and walked into a liquor store and saw Eagle Rare

Single Barrel for $25 and some real expensive bourbon next

to it for $1OO? I’m not even going to think about it, I’m

going to buy four bottles of Eagle Rare!” Getting the

consumer to consider that there might be $1OO worth of value

in that $1OO bourbon is a process that’s going to take some

time.

Maybe it’s a

facing issue: will more brands of a type mean more sales for

a category? Put another way, do future advances for

super-premium bourbon sales depend on line extensions, or

deeper marketing for existing brands? “We’ll see activity in

both,” answered Wayne Rose. “Selling a brand experience is

so important; what a brand stands for, looks like, tastes

like. Line extensions may add value to that, add to the

bottom line, add consumers, but the core brand, the parent

brand, is the one that drives the image of the brand. Vodkas

may be an extreme example. It’s hard to line extend without

a powerful parent brand.”

(That sounds

like a possible line extension in Woodford’s future; how

about it, Wayne? “We’re not ready to announce anything, but

there is work in that area,” he admitted. “That’s all I can

say.”)

Kass, as a

distiller, had some wake-up call words for the high-end

bourbon negociants, selling their picked labels: “As bourbon

heats up,” he said, “there’s less bulk bourbon on the

market. People who were willing to sell off barrels, that

market’s the tightest it’s ever been. As a distiller, you

want to sell what you make. If you can take your barrels and

put them in branded bottles, you make more money and you

build your brands . . . and then you make even more money.”

If bourbon’s hot, no one’s going to be dumping what they

could be making good money on.

There’s still

one factor lurking in the background: the Allied Domecq

purchase. Some brands are going to wind up in new stables;

Maker’s Mark will almost certainly wind up sharing a stall

with Jim Beam. Fallout? Minimal. This is something industry

geeks love to talk about, but no one is going to take a

successful brand and mess with it. Don’t expect anything to

change on your shelf because of this. You may talk to a

different rep and give a check to someone different, but

that’s going to be the only real effect.

What about the

guys in the trenches, what do they see? Is there really

something going on? Gary Park, of Gary’s Liquors in Chestnut

Hill, MA, sees it. “We have had a tremendous uptick in

bourbon sales over the past few years,” he said, “it’s quite

strong, from Jim Beam to the high-end bourbons – the Beam

Small Batch, Blanton’s, Eagle Rare, Wild Turkey Russell’s

Reserve, Elijah Craig 18-Year-Old – it’s all up. Well, some

of the lower-end, bar grade stuff is still just puttering

along. But from Jim Beam, Jack Daniel on up, it just sells

more and more, and it’s to younger people, which I am not

seeing in Canadian whiskeys. I don’t see young people going

there. Bourbon is where people often start before going to

Scotch whisky.”

Neal Zagarella

is the bourbon guy at Vinnin Liquors, Swampscott, and he

sees the growth more focused on the high end. “The high end

is going up,” he said, “the low end is going down, and the

middle brands like Jim Beam are still pretty strong. There’s

more of a single malt kind of clientele, especially on the

high end.”

Sometimes a

whiskey does so well, it grows itself out of the ‘special

purchase’ category. “Maker’s Mark has grown in the last few

years,” said Zagarella, “and now it’s less of a specialty

purchase; it’s a regular thing. If someone came in 5 years

ago and wanted something special for a father’s birthday,

that would have been Maker’s. Nowadays it’s something like

Knob Creek or Booker’s.”

The bourbon

market is finally catching up, and bourbon buyers are

starting to sound like every other connoisseur: “Got

anything new?”

The bourbon

industry is ready. “People will keep coming out with

specialty whiskeys,” predicted Julian Van Winkle. I can’t do

that right now, our supply’s too tight. I do know that

Buffalo Trace is coming out with a couple new things – new

finishes, experimental formulas, unfiltered whiskeys. You

can’t just sell the same old thing all the time. People want

new stuff.”

New stuff from

an old American business, new ideas and profits from an old

reliable category. It ain’t your daddy’s bourbon, and that’s

good news – even for your daddy. He might like a bottle for

his birthday.

|

You Say Rye? “American Rye? Don’t “The “If The What The If It That’s Look “Put Rye “There’s |