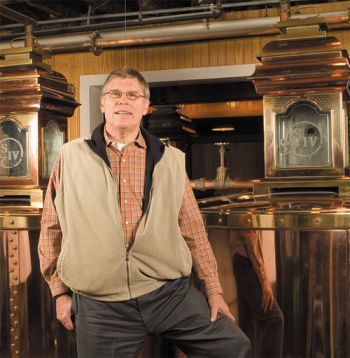

Profile: Bill Samuels

BILL

SAMUELS, Jr. •

67 • President & CEO • Maker’s Mark Distillery

• Loretto, Kentucky

![]()

Tall and rangy

Bill Samuels is steeped in family history, local culture,

yarns, jim-crack anti-promotion, all driven by a deep love

of the taste of his family’s 5O-year tradition of making

fine bourbon. Samuels is lovingly supervising a rebuilding

program at his venerable distillery, restoring buildings

on-site and in the village, and converting an ancient rack

house into a contemporary urban lounge and hospitality

center. He wears his learning in many fields lightly, but

uses all in his work: civil engineering (as above),

physicist (best reason why he came home), law (can talk his

way through a briar patch). His funny, candid, homespun,

bone-dry yarning rambled on about family history, neighborly

competitors and his single high-grade product. A stroll

around the historic landmark distillery with Samuels was

punctuated by tour groups, wax dips, aromas of cooked corn

and creek-side spearmint, and the whiff of a buzz about an

unscheduled visit by a black bear!

![]()

HISTORY

LESSONS Our

family’s historic T.W. Samuels distillery near Bernheim

Forest was built after Prohibition by my granddad; it closed

with the others when Roosevelt mandated that all US

distilleries convert to making industrial alcohol for the

war effort. (Didn’t matter that our still columns were too

short to make 19O proof alcohol, only tall enough to make

13O to 15O proof whisky.) We threw up our hands, and Dad

signed up for the Navy the next day; he was stationed at

Hingham (MA) Shipyard ’til late ’45. (Mom christened the USS

Ramona with a Champagne bottle.) The distillery business

collapsed, the building was left untouched from 1943 ’til we

started using the rack houses in the ‘9Os. So, the war put

us out of the pedestrian bourbon business. When we came

back, we came back with a new notion – a fresh plan – and

essentially led the charge that ushered in the modern era of

bourbon, and put Kentucky in the forefront of the cocktail

culture. So even if it didn’t seem right at the time, we

thank Mr. Roosevelt for making bourbon today’s hot brown

category!

DIM

BULBS This seven

generation Bourbon dynasty was not always easy truckin’. As

I researched the family I found several generations of

incompetence. They carried my great-grandfather at both

ends: his father when he was young, and his son when he was

old. You could get away with that in the old days. Dad was

the only odd-generation male who was reasonably competent;

the others weren’t criminal, just ineffective. Family

business, other than small retail, is a thing of the past,

unless you get sperm-lucky or bring your daughters in. First

daughters tend to be aggressive; I thought mine had the

knack. But it turns out my son Rob has it. When I was in

graduate school in California, I worked at a test base at

Aerojet General on the Polaris missile project. I made a

large mistake, and the rocket broke loose from the test bay

and went into the executive office building. That was a bad

thing and a big one: it made the Associated Press and I got

fired. At that moment I knew I needed to come back and help

Dad. He didn’t want me, so I went to Vanderbilt Law School

in Nashville.

HAP

HELPS OUT After law

school, I wanted to go practice law and accepted a job at

Bendix Company in South Bend. I only came back because of

Hap, Dad’s friend and actual competitor. Hap was Dan Evans

Mottlow, great-nephew of never-married Jack Daniels and son

of Lem, to whom Jack gave the business. Their distillery

office was right across the street from my law school. On

Friday afternoons, we’d go fish, play gin rummy, visit the

distillery. Hap said, “You owe me for puttin’ up with you

for three years. So I want you to spend one year with your

father’s distillery. I think it’s gonna work. Go back and

poke around for a year, then make your own call.” When Hap

talked me into coming back, Dad was prepared: he had work

for me that assured that nothing would blow up. He tried to

be polite and said: “Tell you what, son. I’ll take care of

the distillery and the money, and you git on up to

Louisville and find us some customers.” Though I have a

varied technical career, hardly any of it is in applied

whisky-making. Working for Dad wasn’t too bad, because he

wasn’t a control freak. He saw himself as a visionary but

what he really was was an optimist. They’re very different

animals. Neither one of us thought that the business would

be anything more than a hobby; he’d lied to me when he told

me it was ‘turning a corner’.

MOM’S

HIGH MARKS My mom

(Margie Mattingly) did some things extremely well, looking

at the business from the outside with a consumer’s and

designer’s eye. She had great taste in decorative arts,

graphics, antique furniture, was a foremost authority on

English pewter and the makers’ marks. She designed our

package exactly 5O years ago from a pewter bottle. From her

collection of 18OOs cognac bottles, she took the wax seal

idea as a visual cue. That’s her Star Hill Farm seal, too.

With her chemistry degree, Mom marched to the basement,

threw out my photo lab, and set up a wax test kitchen. She

used the deep fryer – no more French fries – and came up

with a grabby, tamperproof red-wax dip that we use today,

right on the bottling line. The squared bottle shape was a

big departure, didn’t fit in the bar wells. Dad caved in on

the packaging – Mom was the stronger person – but was

worried to death about getting the wax off. He finally paid

people to insert a little ‘pull me’ tab while the wax was

hot, rather than deal with lawsuits when bartenders went to

the knife. My dad’s distilling goals were to remove the

whisky’s bitterness and control consistency. When Dad was

stuck on which grain combination to use, Mom struck paydirt

again, leading the way by baking loaves of bread with

various grains. The eventual surprise winner for whisky

turned out to be red winter wheat (we use 16%) to go with

the corn (7O%) and barley. Her touch can also be seen in the

village restoration and our first press releases.

MARKET

PLAN: 1967 Post-war

bourbon wudn’t a commercial product, but an expression of

Dad’s self. The hard part was communications ’cause Dad was

adamant about not attacking people. Our global business was

17,OOO cases and 16 of it was in Kentucky. Bacardi and

Smirnoff were on the move, and white wine followed in the

‘7Os. Bourbon was out of the race. A marketing plan was

concocted by Louisville advertising guy Jim Lindsay and me.

Our precepts: spread word of mouth; let product speak to

consumers; make taste experience foremost (a hardheaded

idea!). Our game plan: hover, never attack. Our position:

Jack Daniels plus, aimed at mature tastes. Our success

depended on Jack Daniels’, as we’d get their spinoffs. Dad –

disciplined, honorable and pure – could see our results, but

not scrutinize our questionable, even reprehensible

procedures. I was way more commercial than he, not wanting

to disappoint consumers.

JOURNAL

JUMPSTART What

jump-started us nationally was Dan Govino’s wall street

journal article on my father and the distillery’s historic

status in 198O. Restaurants and watering holes perked up and

started to contact us. We put our heads down and tried to

keep up, and we’re still at it 27 years later. In the late

‘8Os, local competitors began to make their own high-grade

expressions of bourbon. Beam’s launching its brilliant

small-batch collection 2O years ago added gravitas to our

staunch stance for product over growth. After the article,

we had to: One, buy time. We had zee-ro distribution; my

sister took phone calls. Keep buzz going until we had more

to sell (one year back-up in the warehouse); Two, field

requests from restaurants and bars and local ‘distributors’.

Bottle at a time; Three, spend time with media, listening to

every phone call and letter; Four, Crank production! Never:

lower proof below 9O, sell below 6 years, buy whisky, and

Five, leak some product to major cities without

discounting!

BOURBON

BARONS There were

really great mentors in this industry. I got a dose of

working with Jack Martin (of the Heublein family, we say

‘high-bline’) who bought Smirnoff for $14,OOO. Mr. Sam

Bronfman – he bought Seagrams before Prohibition – would

come down to [Kentucky] Derby with bottles of Crown

Royal as house gifts before anyone heard of it. Jim Beam was

amazing, too, so good with kids. We lived next door and I’d

spend after-school with The Colonel. He kept a gigantic box

of Lincoln Logs under his bed on the ground floor (had a

hard time with stairs). He’d say, “Build a fire station.” He

was born during the Civil War, and died when I was 7. Over

at Heaven Hill, Larry Kass and Max Shapiro, the first

Kentuckian to graduate first in his class at Harvard

Business School.

EXPORT

PROMO We’re gonna

send Rob up to Harvard Business School so he can take over

when I go into semi-retirement. We put him in charge of

export less than two years ago – essentially going from

zee-ro to something – and it didn’t take him long to figure

out why: it’s tiring. I’ll do 3 to 4 big trips out of the

country a year; our distiller just got back from Japan,

Germany, London. We do half his travel, Rob does the other

half. We didn’t have any whisky for export ’til lately, and

we kept putting off the marketing. Rob figured we’d best go

where the inquiries came from: Australia, England, Japan,

Germany. But it’s still teensy: grown from 2% to 8% in two

years. Stateside there wudn’t much interest outside Kentucky

’til the ‘8Os. When I started, Kentucky was 95% of our

market; now it’s about 7%.

DON’T

MESS with MAGIC

We’ve had double-digit growth every year since 198O. That’s

low double-digit: since we don’t buy whisky from others,

have only one source of supply and only one product, we have

to anticipate 6 or 7 years. Fortunately Dad had the

foresight to anticipate increased production. We’ve always

been leery of expansion, so what we did six years ago – in a

novel yet simplistic (and expensive) way – is to duplicate

the 18OOs distilling equipment so there’s a mirror image

distillery, doubling our output. It’s not just ‘don’t mess

with success’; it also acknowledges that we don’t know

exactly what’s going on, ’cause when the alcohol is in vapor

form, you’re out of control. You think you’ve got control,

because you can regulate temperature and pressure, but it

dudn’t take much to tweak it. The safest way to up

production, was just redo what we did. We went to the

engineering company that made the old equipment, and they

dug out the plans and built another one. We’re replicating a

third one right now. The pot stills are the same dimensions.

Three little distilleries, side by side, all making one

whisky.

BEAT

the HEAT We lease

the Old Fitzgerald distillery’s rackhouses because you can

open and shut the windows. We maximize summer heat by

opening the lower windows and shutting the upper ones. We

don’t do vertical blending, but do rotate every barrel.

Vertical aging is better than flat, but that makes the

material handling job difficult. We’ve got lifts, trucks and

rickers (three ricks per floor). When I first worked here as

a teenager, they hid the rickers, and told us we’d have to

roll the barrels up an inclined plane to get ’em on the

right level. That’s in summer in 12O degree heat! I guess

they wanted to impress me with the idea of going to

college.

GEOLOGY

RULES Water and

grain are the keys to good whisky, notably corn and water

‘familiar with each other’, that is, coming from the same

geological area. The water table is limestone shelf; shale

layers allow a pathway and the faster the water moves the

more it’s super-saturated with calcium. Another key point:

there’s no ferrous oxide. This shelf goes up into Kentucky,

S. Indiana, and tails off into Tennessee. (The Scotch Irish

immigrants in Virginia and Pennsylvania knew how to make

whisky. Governor Patrick Henry’s first three land-grant

offices were right on this limestone shelf. To get land

free, farmers had to raise grain. Stills were all over the

place back then, but today all the good whisky’s made right

back where it belongs: Kentucky, Tennessee. We’re all

playing by the geology rules now, a good thing for

discriminating consumers.)

TRADITION

REIGNS We do the

same thing with our corn and wheat. We don’t buy from grain

elevators. We buy from farms as we’ve done for 5O years, in

delimited regions with the same soil composition. Attention

to detail gets harder as you get bigger. We tested soil

samples, chose areas, and to this day we purchase our corn

and red winter wheat from the same four farms. As we made

two major expansions this decade, we must get our farmers to

expand, too. The upside: we’ve controlled growth and have

more demand than product; and downside: the distillery’s a

registered national historic landmark, so we can’t make

sweeping changes. Our old grist mill was replaced by a new

one that uses not hammers (too much heat gives the corn beer

a burnt sensation) but rollers, which grind coarser than a

bakery mill.

TRUE YEAST This

is another critical component. Dad kept our yeast alive in a

water refrigerator for ten years when we were out of

business. He wasn’t sure if the family yeast was the right

one, because we’d made mediocre whisky before. The

fraternity of other distillers – Hap Mottlow, Jerry Beam,

The Van Winkels, the Brown-Forman folks – were very helpful

in sharing their yeasts, but eventually we went back to our

own.

MASH

& TUN To a

blend of 7O% corn and 16% (most unusual) red winter wheat

(rye is too bitter) and 14% malted barley, we add 25% of

yesterday’s tun leftovers [sour mash]. A little

malted barley is added last because it cooks fast. We don’t

use a pressure cooker, which overcooks the wheat and barley.

All we take from the mash is the carbohydrates; the rich

wort (or spent beer) goes to hogs and cattle. We use only

American white oak, grown in Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas.

Local coopers are Independent Stave and Bluegrass; take a

tour if you can. We drive our coopers crazy because we don’t

trust their kilns for consistent heat. Our oak staves sit

quarantined in a woodyard to air dry for a year. Other than

a nail, nothing taints a whisky worse than a green barrel

stave. It imparts a musty, pungent aroma.

FOURTH

on MAIN When our

former mayor not quite seduced a major developer to build an

entertainment district in downtown Louisville in 2OO4, he

countered by bringing famous local brands to the table:

Louisville Slugger [bats], Kentucky Derby and us.

Our presence was to help revitalize downtown, though we

caught grief at first from neighborhood bars and

restaurants. It’s turned around now. We only asked, one,

that it be the finest bourbon lounge in the country, not a

saloon (they redesigned it), and two, no Maker’s Mark

paraphernalia; we want to showcase all the

bourbons.

MARKET

PLAN: 2OO7 We’ve

just now begun to tap the international market; my son Rob

has raised our ex-US sales from 2 to 8% since 2OO5. We’re

just seeding the market, but it’s not a tease. This is all

we got! Markets today are: California (85K cases, rising),

Kentucky (flat at 65K), Texas, New York, Florida, Georgia,

Oregon and Washington, Tennessee, Indiana, Virginia. Five

years ago we started to experience an undiminished explosion

of visitors: the market has literally come home. Kentucky

Hospitality is the recent key to rebuilding the industry

locally, and all the distillers are on board. We’re changing

and preserving all at once. We’re upgrading two 188O rack

houses at the distillery. One and a third will stay in use

but two-thirds of the second is being transformed into a

modern urban lounge with fancy bar, a Glassworks sculpture

of a big Maker’s Mark bottle spouting “Kentucky Shampain”,

copper colored pillars, brown maple rafters, room for 1OO,

and a sound system for bands.

BOURBON

TRAIL Internal

growth within the bourbon industry has meant more and

broader taste profiles. Our collective concentration on the

pie has served to make that pie grow. “Bourbon Country”

consists of 7 distilleries owned and operated by members of

the Kentucky Bourbon Association. We make the product, still

talk to each other, and we’re taking our hosting

responsibilities seriously. Seven distilleries are on board,

with more to follow: Jim Beam, Heaven Hill (terrific

Visitors Center!), Makers Mark, WIld Turkey, Four Roses,

Woodford Reserve, and Buffalo Trace. Six county judges and

Jim Woods, President of the Louisville Convention Center,

are involved in creating the Bourbon Trail (like Napa with

no train) starting from Louisville as our Gateway City.

Fleshing out the hospitality fabric are B&B’s in

charming communities like Frankfort and Bardstown. Every

venue’s different. Communities embracing the concept include

counties with no surviving distilleries but charming towns,

Danville and Harrodsberg.

PRODUCT

LINE=1 We’ve never

made a second product; front palate finish is our main goal.

We don’t like big, bold bourbon. We’re about whisky, not

bells and whistles. We could never get comfortable with the

idea that blending over-age and under-age whiskys could

create the right product. Our SKUs are few (1.75L, 1L,

75Oml, 375ml, 2OOml [handful], 5Oml minis, mostly

for Kentucky dry-county clubs) and inside is only Maker’s

Mark.

YELLOW

WAX EVENTS Every

bottle is hand-dipped right on the line by ladies who exert

a little personal English. The wax is red, except for

charity event bottlings, nearly all in Kentucky. Our local

leading lady is Sally Brown (Forman), now 96 and strong as

new rope, who set up W.L. Lyons-Brown Foundation, donated so

far $1OO million for preservation, such as the palisades on

the Kentucky River. Maker’s Mark has raised $5 million for

underprivileged children at U. Louisville School of

Education (25OK), Markey Cancer Center at U. Kentucky,

Thoroughbred Retraining Center.